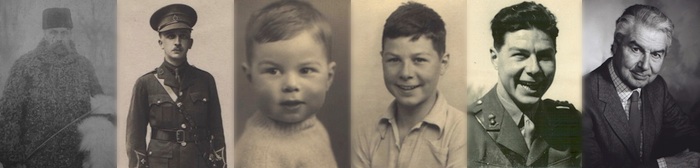

The Mitchells up until 1924 - part 1

My grandfather was a Scot, living in Glasgow, and owned a drapery business. He had married, as a young man in the eighteen-sixties, a striking young woman, Christina Braid. She had been torn between two suitors; a rich young man in Edinburgh, and Alexander Mitchell in Glasgow. She got engaged to the Edinburgh man, but half-way to Edinburgh, she changed her mind, stopped the carriage, and went back to Alexander Mitchell. They married, and happily together had nine children. My father, David Robertson Mitchell, born in 1881, was the second youngest.

The business that Alexander returned to in Scotland must have been fairly prosperous, because, of the boys in the family, one went to sea and became a master mariner, one became an engineer with the ship-builders, John Brown; and two, David and James, became doctors. And this all had to be paid for -- there were no grants in those days.My father David went to Glasgow University and Glasgow General Hospital, and eventually qualified in 1904. But he interrupted his studies as a medical student, by volunteering for service in the Boer War. He served as a dresser (i.e. what would now be called a paramedic) in a military hospital in South Africa for about a year, and was thereafter always justifiably proud of his Boer War medal. While he was out there, he learned to ride, which stood him in good stead in his early days in general practice.

When he finally qualified in 1904, he went to India as a ship's doctor. In those days it was a long slow voyage, and they dressed for dinner every night, in true British Raj fashion. So before he left, he bought dozens of starched dress shirts to see him through the voyage -- such a supply that he was still using them 30 years later. He saw India in the high days of British Imperial rule, added it to his list of experiences, and came home. He then , like so many Scots did , came south to earn a living.

At the age of 24 he became assistant to a general practitioner in Blaenavon, Mon. The GP was Dr. Alfred James, a bachelor in his late thirties, a Welshman of considerable eccentricity and dash, a great drinker, and in general a much admired and loved pillar of the colliery town which he looked after. The patients were colliery workers. The terrain was a bare moorland area at the head of the valleys, overlooking an escarpment to the north beyond which was the beautiful Brecon hills and valleys.

The rather solemn young Scot, David, fitted into this society pretty well, if occasionally with some surprise. He remembered having frequently to drive the horse and trap down to the pub to bring his paralytic boss home. But he enjoyed the life; there were many satisfactions in general practice among the Welsh miners and their families, who were open in showing appreciation. He was a good doctor, a good listener, and his rounds on horseback or in the trap kept him happy and fit.

In 1910, he got the chance of a partnership with Dr. Warren in Abersychan, further down the valley towards Pontypool. With this partnership came a house in the High Street - a house with several rooms, a garden, and a yard at the back with a small coach-house and stable. In those days the area was extremely prosperous on coal, and the young man settled in his house, with a housekeeper, a groom, and a horse and trap. He must have felt thoroughly established; the social life was excellent, particularly for an unattached bachelor. He met several girls, but never one that he really fell for. I once came across a photograph of a very attractive Edwardian girl, and his comment was "Ah yes, a lovely girl from Newport. But she had cold hands". I wonder, if she'd had warm hands, where would we all be now?